The data presented up to this point has encompassed all entities reporting to the CEB – in other words, the entire UN system. Figures 13 to 18 shift the focus to the UNDS, which comprises a sub-set of entities mandated with promoting sustainable development and human welfare in developing countries and countries in transition. More concisely, these entities concentrate on development and humanitarian assistance, which are together referred to as UN OAD (see definitions in Box 2).

Contributions to UN development and humanitarian assistance amounted to US$ 45.6 billion in 2023, or 67% of total UN system revenue. This represented a contraction of 16% (US$ 8.9 billion) compared to 2022 amounts. Breaking down the 2023 figure, 81% of funds were earmarked contributions, while 19% derived from assessed and voluntary core contributions (which together constitute core contributions).

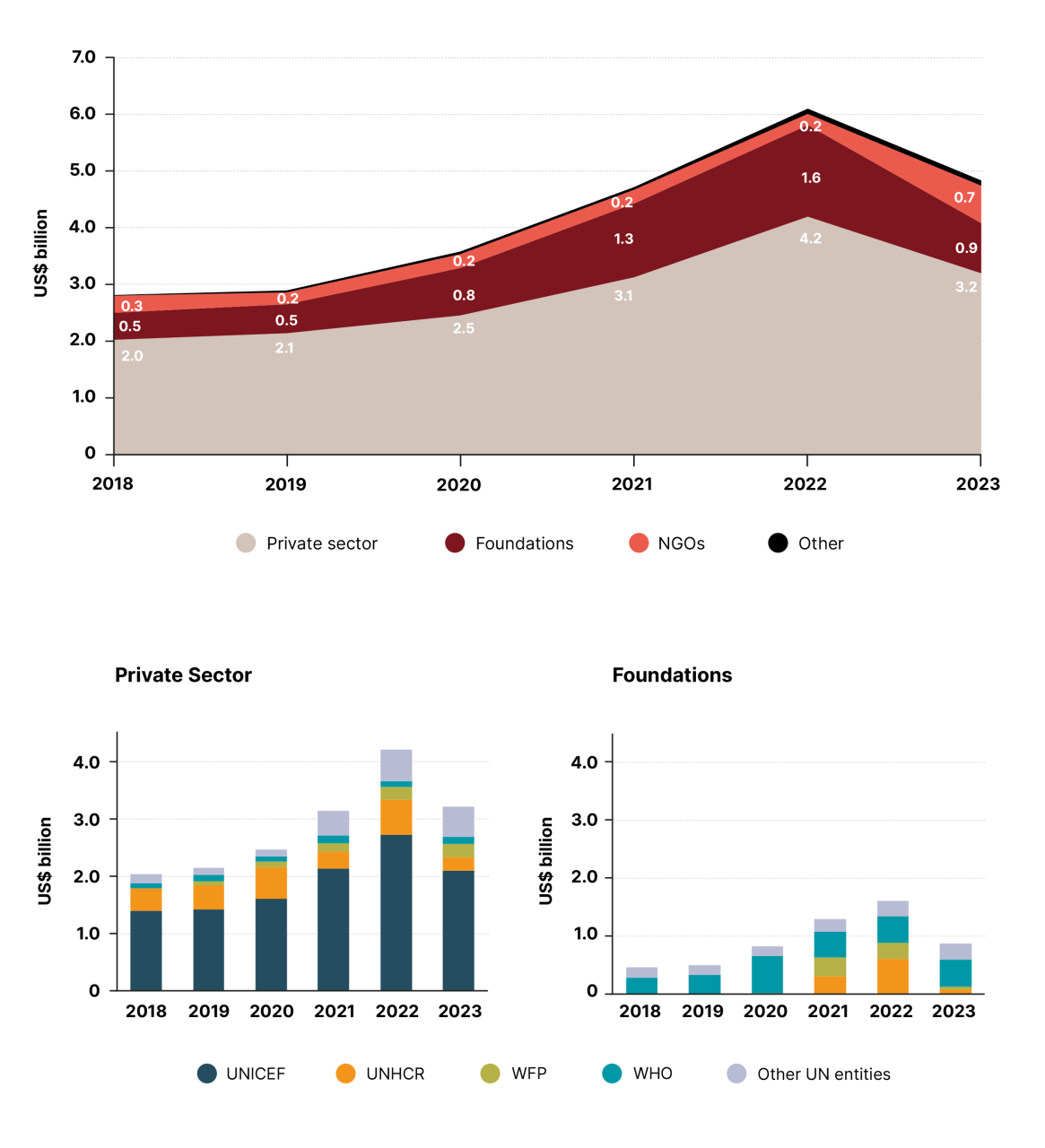

Other non-state funding to the UN system, 2018–2023 (US$ billion)

Source: Chief Executives Board for Coordination (CEB).

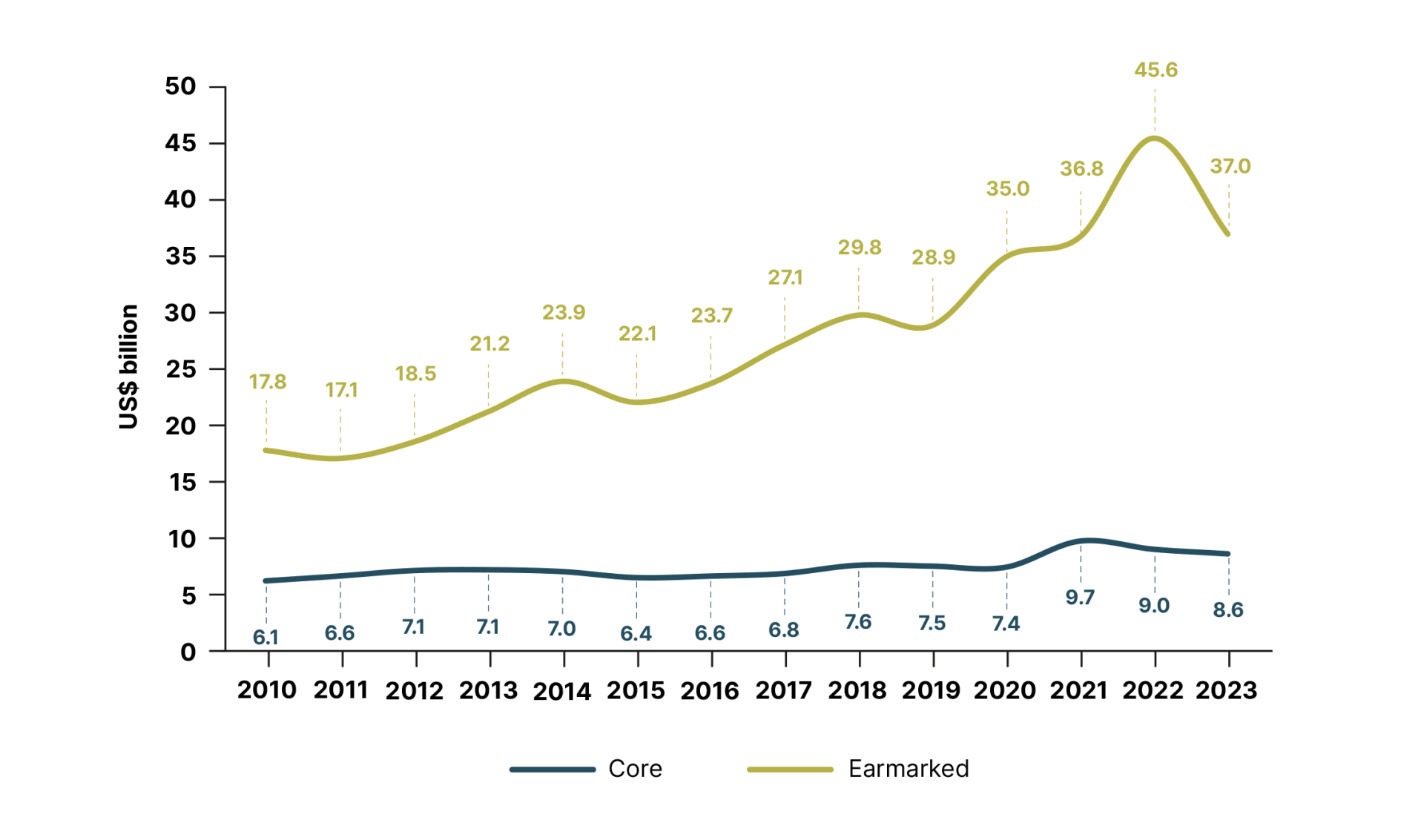

Figure 13 illustrates the evolution of core and earmarked UN OAD contributions from 2010 to 2023. The overall growth of UNDS revenue during this period was largely driven by substantial increases in earmarked funding, which rose from US$ 17.8 billion in 2010 to a peak of US$ 45.6 billion in 2022, before dropping to US$ 37 billion in 2023. This US$ 8.6 billion decline (nearly 19%) compared to the previous year is reflective of shifting donor priorities, including the effect on donor budgets of broader geopolitical and economic pressures.

Total core and earmarked contributions for UN development and humanitarian assistance, 2010–2023 (US$ billion)

Source: Report of the Secretary-General (A/80/74-E/2025/53). Historical data from various reports.

By contrast, core contributions have remained relatively stable over the years, rising steadily from US$ 6.1 billion in 2010 to US$ 9.7 billion in 2021. More recently, however, core funding for UN OAD declined to US$ 9 billion in 2022 and further to US$ 8.6 billion in 2023. The decrease is mainly explained by reductions in voluntary core resources, as assessed contributions have remained steady. These trends highlight the challenges faced by the UNDS in mobilising flexible, predictable funding in support of operational activities.

The gap between core and earmarked funding has widened considerably since 2010, increasing the imbalance in funding modalities. This disparity represents a challenge to UNDS capacity, both in terms of responding flexibly, effectively and in a coordinated manner to global needs, and when it comes to investing in long-term development solutions. The 2024 Report of the Secretary-General sets out the situation as follows: ‘When non-core funding accounts for a high proportion of overall funding, it can lead to the fragmentation of resources, especially if the non-core resources are tightly earmarked for specific projects. High proportions of non-core funding can also promote a culture of United Nations entities competing for donor resources.’30

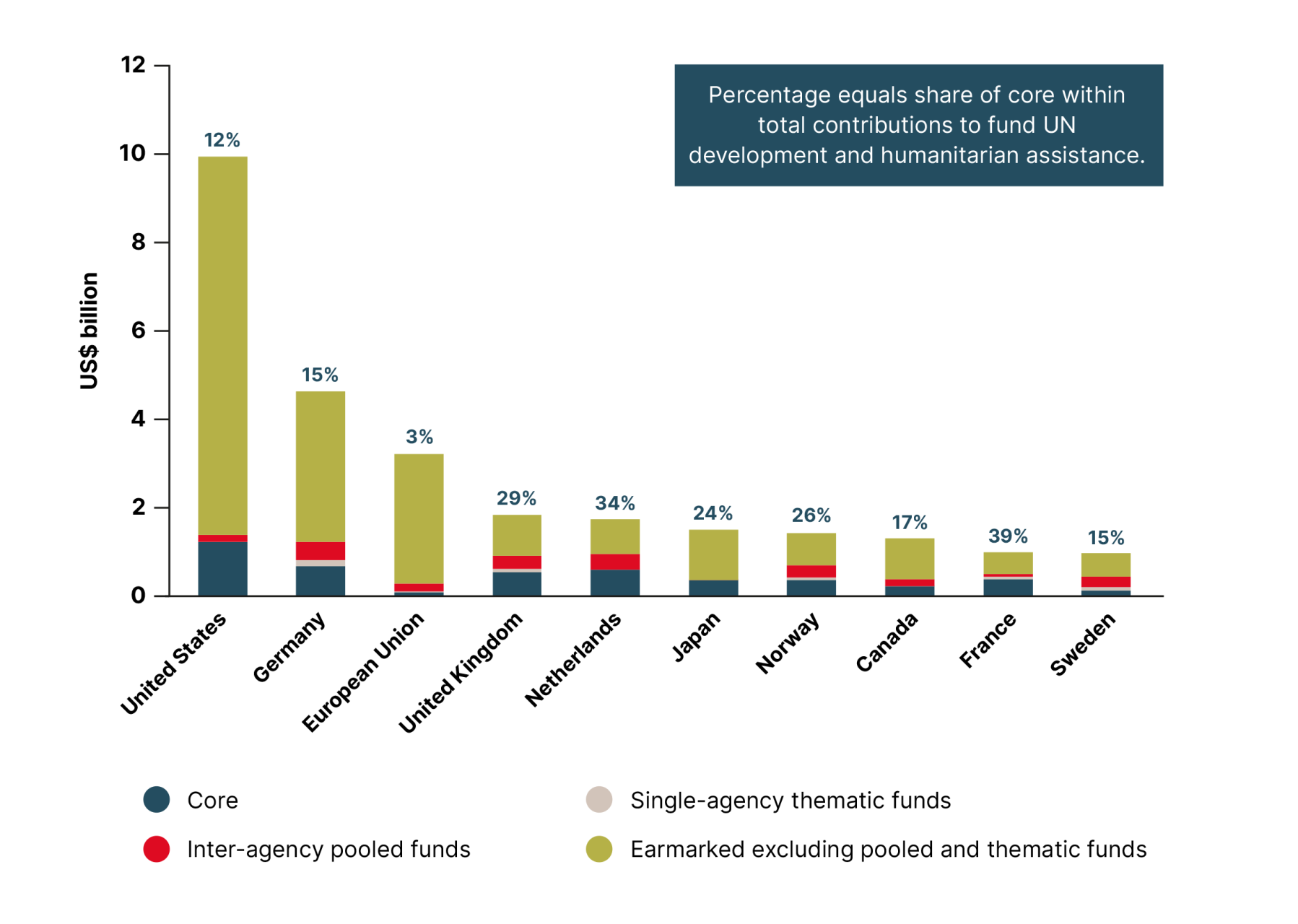

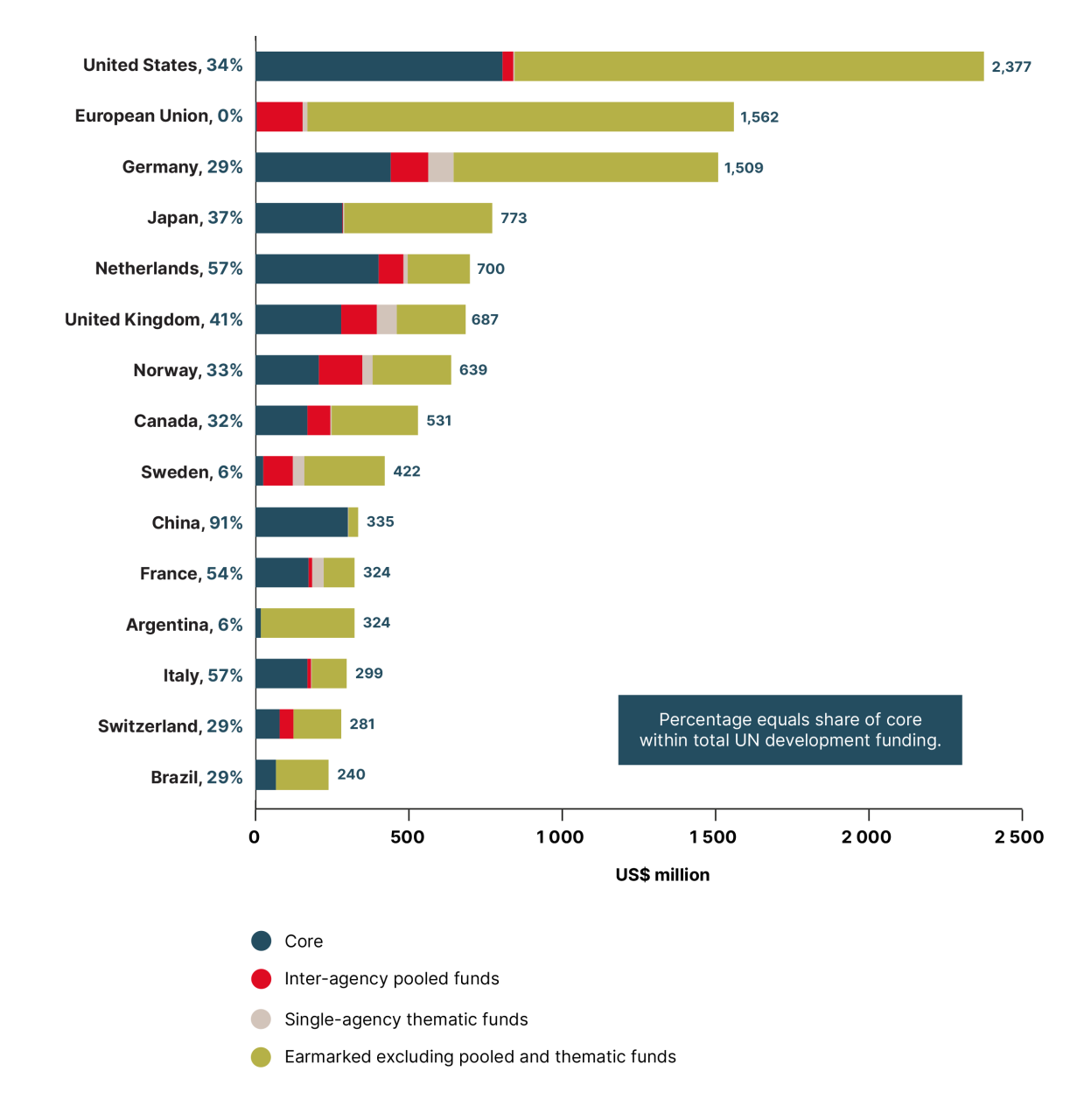

As Figure 8 demonstrated, the UN system revenue relies heavily on a small number of contributors. A similar pattern is true for the UNDS, with the top ten OECD-DAC contributors collectively accounting for 61% of overall UN OAD funding in 2023. There are, however, notable variations in the choice of financing instruments among these donors, as illustrated by Figure 14. The percentage labels indicate the share of core contributions within each donor’s total contribution, while earmarked resources are further broken down in order to distinguish earmarked funding through single-agency thematic funds and inter-agency pooled funds. As mentioned, the EU’s legal and institutional status as a political and economic union of member states means it mainly provides earmarked contributions.31

For nearly all top ten OECD-DAC contributors to UN OAD, the largest share of their 2023 contributions constituted earmarked funds not channelled through pooled or thematic funding modalities. The United States remained the largest donor in absolute terms with close to US$ 10 billion in contributions, 12% of which were provided as core resources. France and the Netherlands allocated compar-atively higher shares of their contributions as core funding, at 39% and 34% respectively.

Figure 14 highlights how the top OECD-DAC contributors to UN OAD differ not only in terms of volume of contributions, but in their funding mechanism preferences. Here, Germany, Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Norway and Sweden show more diversified funding profiles, with notable shares of pooled and thematic funds offering a valuable complement to core resources.

Funding composition for UN development and humanitarian assistance: Top OECD-DAC member state contributors, 2023 (US$ billion)

Source: Report of the Secretary-General (A/80/74-E/2025/53).

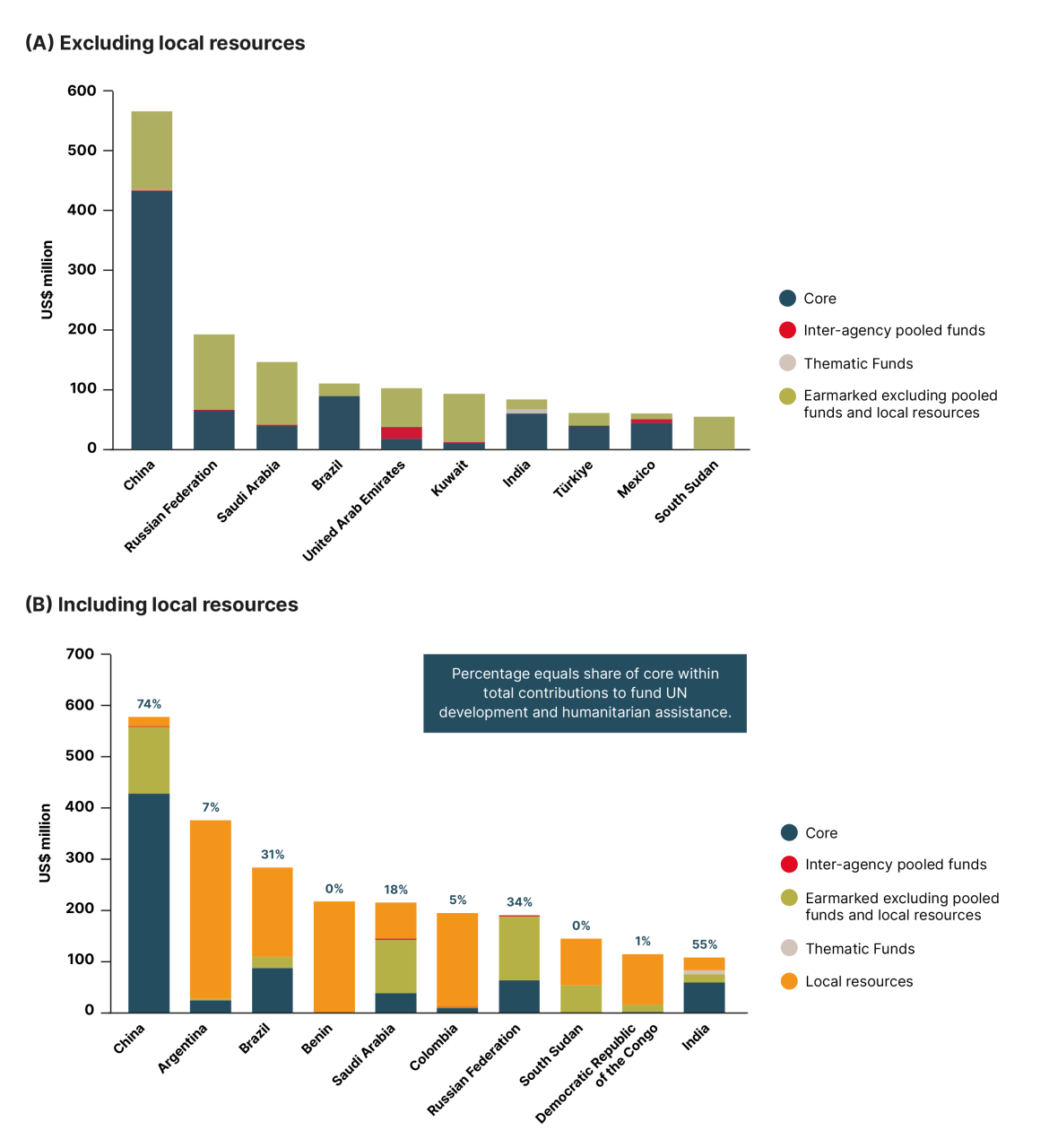

Emerging donors also exhibit a diverse UN OAD funding mix, with most countries contributing a comparatively higher share of core funding. The two charts in Figure 15 present the contributions of the top non-OECD-DAC member state contributors to UN OAD in 2023, distinguishing between funding that includes and excludes local resources.

Funding composition for development and humanitarian assistance: Top non-OECD-DAC member state contributors, 2023 (US$ million)

Source: Report of the Secretary-General (A/80/74-E/2025/53).

Local resources refer to earmarked contributions from UN programme countries, financed through domestic govern-ment budgets, in support of that country’s own national development frameworks.32 Looking at the ‘excluding local resources’ chart of non-OECD-DAC contributors reveals limited contributions to single-agency thematic funds. Overall contributions to UN inter-agency pooled funds are also modest among this group, although the United Arab Emirates represents a notable exception, contributing US$ 15 million to the Syria Humanitarian Fund and US$ 5 million to the UN Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF).

China is the largest non-OECD-DAC contributor to UN OAD in both charts, providing more than US$ 585 million in 2023, of which a remarkable 74% is core funding. India also distinguished itself by contributing 55% of its total support as core funding. Other major contributors, including Brazil, Saudi Arabia and the Russian Federation, primarily chan-nelled their support through earmarked resources, reflected in core funding proportions ranging from 18% to 34%.

The inclusion of local resources has a notable impact on the top non-OECD-DAC contributors’ composition and ranking compared to when they are excluded. Over 86% of contri-butions to the UN from Argentina, Benin, Colombia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo are local resources.33 Overall, Figure 15 highlights both the engagement of non-OECD-DAC contributors and the continued diversity in funding practices among the group, particularly the balance between core and earmarked modalities.

Figures 16 and 17 show the 2023 composition of the top 15 contributors (UN Member States and the EU) to, respectively, development and humanitarian assistance – the two components of UN OAD. While the distribution of funding modalities varies between the two functions, both reveal a high concentration of contributions among a limited number of donors.

The top five contributors for development assistance in 2023 – the United States, the EU, Germany, Japan and the Netherlands – collectively accounted for 37% of total contributions. When expanded to include the United Kingdom, Norway, Canada, Sweden and China, the top ten donors together provided 51% of total development assistance. For most of the featured contributors, the bulk of development assistance is provided as earmarked funding. Some, such as Germany, the EU, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom, make notable use of UN inter-agency pooled funds, contributing to more coordinated, system-wide approaches.

Recognition of the fact that more sustainable, predictable and coordinated financing is needed to provide cohesive, high-quality support at scale led to consultations being initiated in October 2023 on a revitalised Funding Compact to replace the 2019 iteration. In doing so, the hope was to strengthen the partnership between the UNDS and Member States. The new Funding Compact, endorsed by the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) in July 2024, duly offers a revised set of commitments designed to guide funding decisions, such as increasing both core contributions and UN inter-agency pooled fund contributions. It also sets out measures aimed at further strengthening results reporting, transparency, visibility and accountability.34

The 2024 Funding Compact (also known as Funding Compact 2.0) sets clear targets for rebalancing funding modalities by 2027. One key objective is raising the share of voluntary core funding for OAD provided by Member States from a 2022 baseline of 11.6% to 30%. Similarly, a significant increase in voluntary non-core contributions provided through single-agency thematic funds is envisaged, from 6.1% to 15%, while contributions channelled through UN inter-agency pooled funds are targeted to grow from 8.9% to 30%. In addition, annual financial targets have been put in place to ensure key pooled funding instruments can deliver timely, rapid, predictable support: US$ 500 million each for the Joint SDG Fund and the Peacebuilding Fund, and US$ 800 million for country-level multi-partner trust funds (MPTFs) supporting UN Sustainable Development Cooperation Frameworks (UNSDCFs).35

Funding composition for UN development assistance: Top Member State contributors and the EU, 2023 (US$ million)

Source: Report of the Secretary-General (A/80/74-E/2025/53).

On the humanitarian side, the concentration of funding among relatively few contributors is even more pronounced. The United States provided 28% of all humanitarian funding in 2023, while the top five contributors – the United States, Germany, the EU, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands – accounted for 54%. When expanded to include Norway, Canada, Japan, France and Sweden, the top ten donors’ contribution to humanitarian assistance together amounted to 67%.

Figure 17 illustrates the funding composition of the top 15 contributors to humanitarian assistance channelled through the UNDS in 2023, disaggregated by funding modality. Across all 15 contributors, the share of core and single-agency thematic funding is limited, highlighting a persistent gap in the availability of flexible, predictable funding for humanitarian operations. Despite their recognised impor-tance in enabling coordinated responses, UN inter-agency pooled funds continue to be underutilised by most donors. This trend contrasts with the commitments made under the Grand Bargain – an agreement between some of the largest donors and humanitarian organisations – which advocates collaborative planning and funding mechanisms conducive to cross-sector collaboration, as well as innovative financing approaches fit for use in protracted crises.36